Introduction

Fourteen years ago, on the digital canvas of my first blog, I penned a piece titled Jackie & June. Little did I know then that this humble beginning would evolve into a cornerstone narrative, a pivotal chapter in my memoir, A Time to Mourn & A Time to Dance. Recently, an email arrived from a man I met in 2010, a devoted reader who has followed my work for years. His request, simple yet profound, reignited memory and inspiration, prompting this reprise. This is for Cousin Adam because he asked.

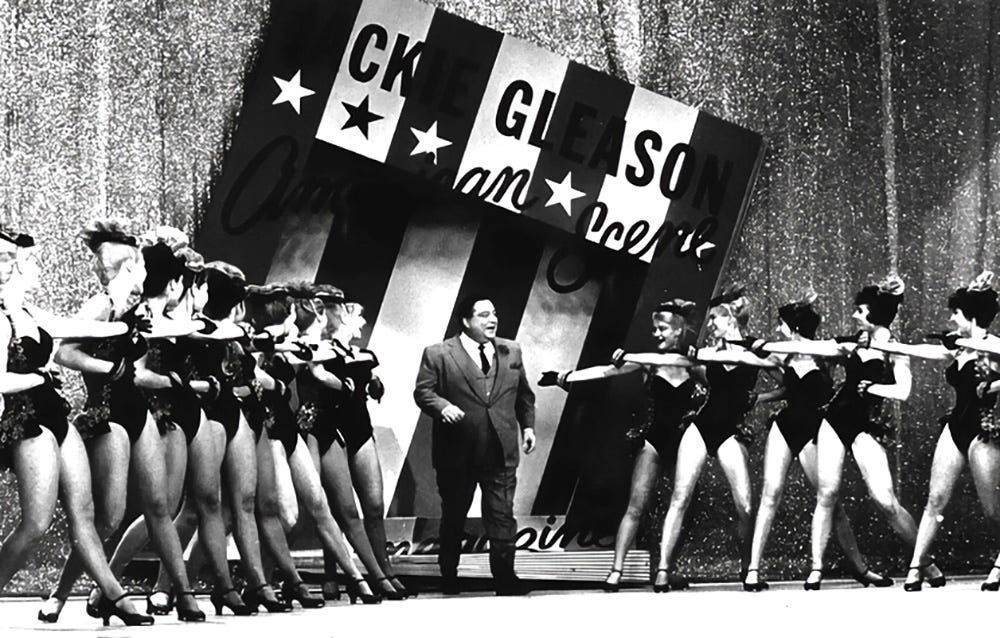

Jackie Gleason, June Taylor, and the June Taylor Dancers—these were names that lit up television screens and stages, the icons of a bygone era. Yet, this brief homage barely scratches the surface of the rich tapestry of stories and experiences that unfolded sixty-two years ago during what I affectionately refer to as Camelot. So, dear reader, as you settle in with a steaming mug of coffee or tea (for this is a tale that spans the length of a pot), immerse yourself in a slice of American history that may be forgotten by many, especially the young, but remains vividly memorable to those of us who were either active participants or devoted fans.

The Audition

Only sixteen dancers were chosen when it was over. Though 750 dancers appeared for the grueling three-day open audition, hundreds were eliminated through tests of stamina and specific dance requirements, including equal proficiency in tap, ballet, and jazz. We were expected to learn complex dance combinations quickly and accurately. This rigor and pressure for six or more hours each day was gladly endured, for if any one of us showed signs of fatigue, we soon learned that that dancer would not make the next round of tests. Our ability to kick high and steady for long periods was only one of the tests we had to pass in order for the most ‘skilled’ dancers to emerge, based on unknown criteria of the choreographer June Taylor.

It was our third day and the final hour of The Audition. A large, round electric wall clock with thick black Roman numerals on a white face hung next to an old stained standpipe. It was four o’clock. Out of the seven hundred and fifty dancers who arrived three days earlier, only twenty-one remained. It was a sultry August afternoon, and we were in the mud-brown basement-cum-audition room of the Henry Hudson Hotel on West 57th Street in New York City circa 1962.

We were informed that Jackie Gleason was en route from his penthouse suite to help in the selection of sixteen female dancers. Along with being physically and emotionally weary, our leotards were saturated with sweat, wet hair clung to our heads and necks, and little of our facial makeup remained due to the previous five hours of executing an endless series of dance combinations.

I heard him before I saw him. Jackie, talking to colleagues, strolled through the double glass doors that opened into the basement. He held a teacup and saucer in his right hand and a cigarette in his left. I was struck immediately by his gracefulness, almost as if he were gliding rather than merely walking. His curly, raven-black hair, only slightly tinged with silver at his temples, set off light-blue eyes that reflected a spirit filled with both joie de vivre and an indefinable sadness. He wore a gray suit with a crisply starched white shirt, and his necktie was slightly loosened. A boutonnière, an ever-present carnation, was in his lapel. He smiled at us and said something, but with my heart pounding loudly in my ears, I couldn’t hear him. I knew that within minutes, we would know which five dancers would be dismissed.

Jackie and the producer of the show sat with June Taylor at a long makeshift conference table. My gaze was fixed on June’s slender five-foot-seven body when she stood up from the table and bent her short, bobbed blond hair towards Jackie to confer with him. Periodically, she cast her pale, piercing blue eyes in our direction. She began shuffling some of the dancers around in the line, asking a few to move up or down by one or two positions. And then, silence.

June held a yellow legal pad containing pages of notes and asked each of us to step forward and give our names, making further notations. Jackie continued smoking his cigarette while looking intently at the dancer, speaking her name aloud. When it was my turn, I thought my voice sounded small, weak, and void of any signs of life. Indeed, in that singular moment, I believed I diminished all merit I might have gained throughout the three-day audition. Then, June called out the name of a dancer and asked her to step forward. When she called out three more names, I was sure these dancers now being assembled were those that had been chosen for the show. When she called out a fifth name, all was still. Breathing stopped as we held our breath. June, with eyes steadily focused on the group of five, walked up to each girl, shook her hand, said thank you, and dismissed them. Long, quiet exhales followed.

Sixteen of us stood there with rampant emotions, from happiness to relief that it was over. It soon became apparent, however, that we were not yet finished. June asked us to perform the dance combination we learned earlier once again for Jackie, involving a protracted series of high kicks. We moved into what would become our almost-permanent positions in the line as June gave the piano player a fast five, six, seven, eight. We pulled ourselves out of weariness into peak performance and kicked high for a seeming eternity until the music stopped.

Jackie applauded while we, with our hands on our hips trying to look matter-of-fact in our demeanor, inhaled deeply to regain normal breathing. When I recaptured my equilibrium and looked up again, I saw June making notes, imagining she was assessing what we had done right, what needed improvement, and who among us required more skill. I shifted my focus to Jackie. His blue eyes beamed approval, and with a wave of his right hand, still holding an ever-present cigarette, he said, It’s going to be one hell of a ride, girls, one hell of a ride. How sweet it is!

We were to become The June Taylor Dancers, opening Jackie Gleason’s American Scene Magazine Television Show from New York City on CBS every Saturday night from 1962 to 1964. The sixteen dancers selected ranged in age from eighteen to twenty-six and in height from five-foot-three to five-foot-seven. I was one of the eighteen-year-olds amazed at my good fortune, for I was fresh off the Greyhound bus with my mother in tow from Cleveland, Ohio, having arrived in New York City only two months earlier.

Work Begins

Of course, our first official workday began with rehearsal. June strode with purpose into the rehearsal hall to begin the work ahead, wearing a lavish sable coat casually draped over her shoulders, which only partially covered her black leotards and tights. Like Bette Davis in the movie All About Eve, she tossed her coat onto a chair, but it fell to the floor as if it were merely an incidental old scarf. She didn’t bother to pick it up. Instead, she lit a cigarette, grabbed some white papers, and gathered all of us to the center floor to sit in a circle. June straddled a weathered oak stool and laid out the ‘rules of engagement’ in a voice not unlike that of a coach at half-time.

This is a team. There will be no individuals. You are here to work in perfect precision. There will be no arguments amongst you. When you arrive at the theater on videotaping day, I want you dressed as ladies, not looking like tired, over-the-hill, and run-of-the-mill chorus dancers with messy hair, no makeup, and sloppy clothes. You will do nothing publicly to embarrass Jackie or me. In addition to the long, hard days of rehearsal ahead, you will be expected to take your dance classes and work on your limitations as a dancer. Even if you make it through the first season, you are not guaranteed a position next season. You will audition again. Do not gain weight, or you will be fired. Let’s get started.

June stepped down from the stool, reviewing the white papers with notes and drawings discernible to her alone that she had made during televised football games. June developed many of our dance combination patterns by watching football plays, expanding them into our dance formations with her unique tools of the trade: dancers, music, lights, cameras, costumes, and vision. At the start of each week, June began rehearsals with a core combination of a new dance routine. Once she was satisfied with the first dance combination, others were developed, discarded, and reincarnated at the speed of light.

Our rehearsal hall for the first season of the show was in the garishly lit basement of the Henry Hudson Hotel, where our three-day marathon audition was held. The basement presented two physical challenges: we were without natural light for most of our waking hours, and the floor upon which we danced was concrete. Dancers and athletes know that when one jumps and lands on concrete, it creates whiplash to the spine, for there is no ‘give.’ Adding that to the potential peril of our bodies years later, with extended arms and legs, we rolled and stretched repeatedly on the concrete floor to create the geometric designs for the overhead camera used for videotaping the live performance. Our vertebrae protruded from our skeleton-thin bodies covered only by a thin layer of skin and a leotard. What this produced by week’s end was a succession of bruised and bleeding bones down our spinal columns camouflaged for the performance. Fortunately, the cameras were never close enough to capture little flesh-colored Band-Aids that our wardrobe mistress neatly applied to each sore and tender backbone.

The scents permeating our rehearsal hall were Jean Naté mixed with a heavy dose of Ben-Gay. Our muscles were sore from the strenuous demands made on our bodies, and we reeked from the sweat that poured out of us for eight hours a day, six days a week. I was almost incapable of walking up and down the subway steps in the first weeks, and my plié at the ballet barre was so painful that I wondered if I would ever be able to reverse it and straighten my legs again.

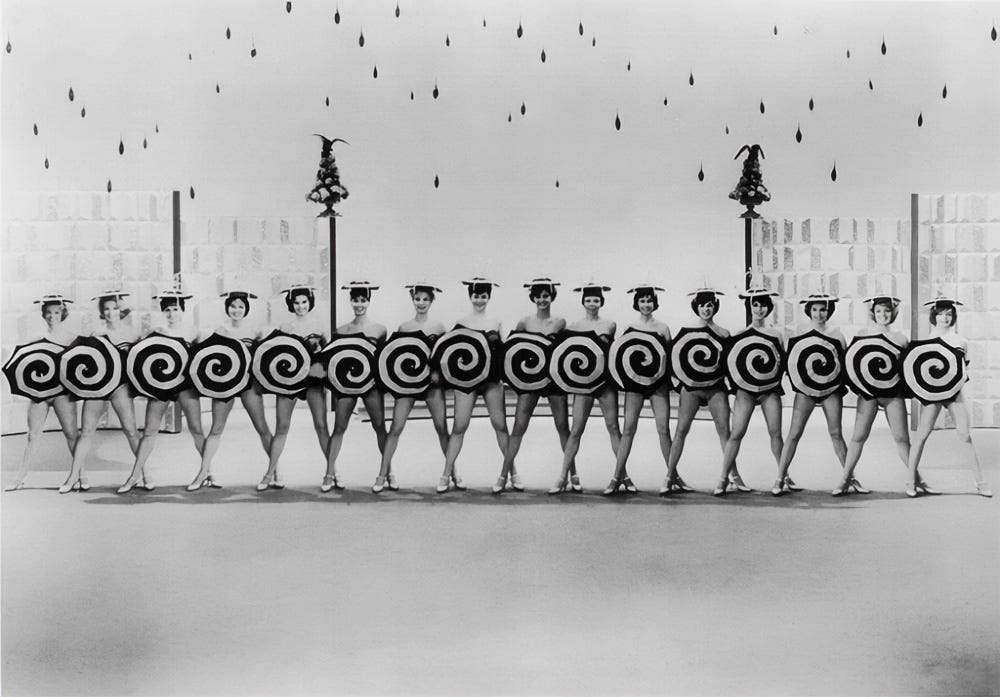

During those long, rigorous days of our rehearsals, we had a one-hour reprieve set aside each week to visit the costume designer for our fittings. Part of the mystique of The June Taylor Dancers was the costume extravaganzas, created each week anew to resonate with the themes of our dance routines, such as our Spring classic using the song Pennies From Heaven as the backdrop for our dance routine—and costumes. These were designed to be a ‘tease,’ for they were strapless. We used umbrellas with a swirl design to cover our bodies throughout the dance routine as we turned, twisted, and manipulated the umbrellas and their design for a dizzying effect. And, not unlike Gypsy Rose Lee, we only exposed glimpses of our bodies and costumes.

My favorite costume, however, was the one we wore for our Christmas show. It was designed to replicate every detail found on little toy soldier dolls with their red, black, and white uniforms accented with gold trim. What made this magical for me was our makeup. To ensure that we did indeed look like little dolls, each of us spent extra time applying perfectly round, red-rouged circles on our faces.

Camelot

On the sixth and final day of our workweek, we did a dress rehearsal and the actual videotaping, logging fourteen to sixteen hours. We taped our shows at the old Ed Sullivan Theater, which encompassed almost an entire city block from West 53rd to West 54th Streets between Broadway and Eighth Avenues. Though our show was the first on CBS to use videotape, we nevertheless performed for a live studio audience. There was no canned applause, and Jackie needed no canned laughter.

Even after a long week of enduring strained muscles and fatigue so intense that I went to bed many nights without eating, the rewards of this sixth day, from dress rehearsal to performance, were my sustenance. I was in Camelot.

My eyes welled up with tears the first time, and every time I heard Jackie’s theme song, Melancholy Serenade, played to signal the opening of the show. There was a do-or-die thrill, a combination of raw nerves and excitement, that spread through my body when the large, black, rolling cameras focused their red lights on us as our dance music struck its first chords. Over the years, I learned how fans gathered in their living rooms at precisely 8 o’clock so as not to miss our three-minute dance performance. Sammy Spear’s Orchestra, live in the studio, played 40s and 50s big-band music.

The waves of cheers and applause from the audience that grew throughout our demanding routines provided us with even more precious energy. I felt the audience’s mounting anticipation for the thirty seconds in our routine when we created the kaleidoscopic floor designs filmed with an overhead camera á la Busby Berkeley. Their excitement was palpable as they waited for that final moment when we rose from the floor and rushed to center stage to form the kick line that presented a vision of unified precision in a fleeting moment of perceived perfection. Exhilaration and relief engulfed us when our music reached its climax, our lungs aching for air. Yet, one more action demanded completion: to create the well-known split in our formation, eight of us on the left and eight on the right with sixteen pairs of hands extended back towards a red velvet curtain where Jackie made his entrance. The studio audience went wild with applause, yelling when they finally saw this handsome, gentle giant of a man who could make them laugh one second and cry the next.

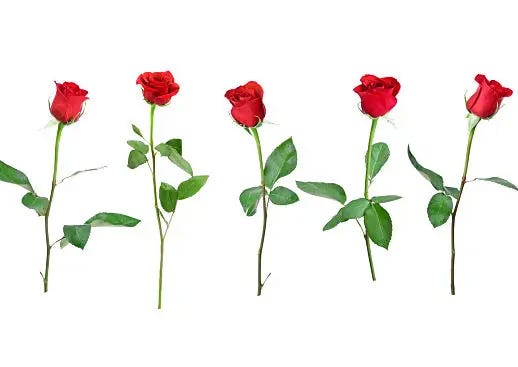

Jackie loved grandeur, extravagance, and glamour. After every show, sitting at each of our places on the narrow, seventeen-foot makeup table was a long, glossy white box wrapped with a large, lush red satin bow. Nestled in this box were one dozen neatly layered, long-stemmed American Beauty roses. Jackie’s generosity was embedded in romanticism: he wanted us to exit the theater with our arms filled with flowers. And so they were there—every week, without fail. It was a simple gesture touched with style, not unlike his unexpected visits during our long rehearsal days at the hotel.

Jackie could visit us anytime, but when he did, he did it with flair. As he entered the rehearsal hall, at least two waiters with carts of freshly brewed coffee, delicately made pastries, and Champagne followed him. June was never happy about this because of her adamant rule that we not gain weight. But we nibbled and picked and sipped anyway. Only when we showed Jackie our new routine were the carts removed, allowing no further temptations.

All Good Things ….

The moments of those first weeks, like a tapestry woven from time, unfolded into four seasons. Jackie finally decided to leave New York and do the show from Miami. June was kind enough to ask me if I wanted to join them, but I said no. I was in the throes of acting studies and did not want to leave New York.

On August 1, 1964, at the end of our final season together in New York City, I stood on a humid train platform in Penn Station and watched many of the people with whom I had worked for the past two years board the train to Miami. Jackie brought his musicians to play on the train for its overnight journey to Florida, and, of course, Champagne started flowing for his entourage of one hundred people. As the train began pulling away from the platform and out of the station, I heard the musicians from inside the cars begin the first strains of Melancholy Serenade.

Epilogue

Jackie Gleason and June Taylor are gone now. There are no collectible DVDs, even VHS videos, where one can see The June Taylor Dancers in their dazzling dance routines and costumes except for those locked in the vaults of the Museum of Broadcasting in New York City.

We exist only in the memories of those who remember.

The reservoir of moments during those extraordinary years created an accumulated wealth of rich and vital experiences—a weathered oak stool and sable coat; a teacup and saucer; a boutonnière worn by a gentle giant; Champagne on rolling carts; a large, round black and white wall clock; long hours of sustained practice in search of perfection; sore, aching muscles that never seemed to go away; distinctly different smells between the Ben-Gay of the rehearsal hall and the blend of French perfumes on videotaping day signaling the shift from preparation to performance; the sweet scent of red roses, and sixteen female dancers sitting at a long table staring into mirrors while applying perfectly round, red-rouged circles on their faces.

Jackie was right. It was one hell of a ride, and, yes, it was sweet.

With affection, love, and humility ~

Postscript: Some of the dancers are still in touch, and I am grateful that after sixty-two years, Jari, April, Phyllis, Donna, Joan, Barbara, and Mercedes are available to reminisce with me. I do not know if my memories match theirs, for we each had our private experiences. My details are what I recall. Theirs may vary. And the other dancers? I searched for a couple of years to find as many of our group as I could. These are the women I found, and I am grateful.

Notes:

Lee Anne, this is such a wonderful story, both for us, your readers, as it must be for you when you recollect these heartwarming memories. I imagine that when the train departed New York, and you could hear the music coming from inside, part of you must have wanted to run after the train and jump aboard. How sweet and exciting to have been part of a such a special piece of history. I think I recognize you in two of the photos. Thank you for sharing this great story.

I remember reading this story many years ago and loved it again today as much as I loved it the first time. Are you visible in either of the two pictures posted?